November 5, 2019

November 5, 2019

by Ted Rau PhD., CPS Partnership Community

Most of my work is teaching and coaching in the context of a governance framework called sociocracy. Sociocracy combines a decision-making method (consent) with a team structure (linked, nested circles) and a strong commitment to continuous improvement. It is designed to optimize human connection, equal voice and effectiveness.

In this post, I want to focus on one aspect of that and how it relates to partnership at eye level. In my work with teams, I notice that the definition of consent as well the explicitness of a decision-making method contributes to their relationship in more than one way.

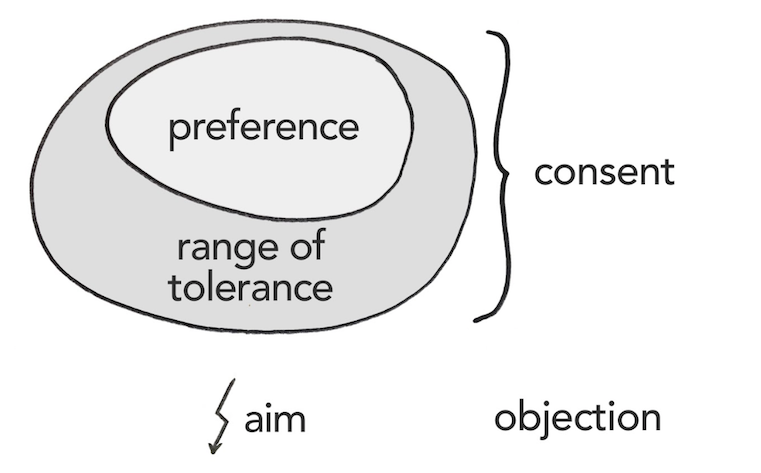

Before we start: the definition of consent in sociocracy is the following: if you bring a proposal for our group, any group member can object to the proposal if (and only if) they see likely harm of the proposal for the group’s purpose. That means, a proposal does not have to fit into everyone’s preference but it’s enough not to see any harm. That’s a fine but very relevant distinction as I will explain now.

Dare to object

Dare to object

Let’s say someone proposes something and the time comes to approve the proposal by consent. Everyone loves the idea. You have an issue with it because you see how the idea creates a problem in a different area. What do you do? Objecting to someone’s proposal is uncomfortable if we see it as a “no” to their idea. Yet, that’s not what objections are. Objections are, by definition, not based on personal preferences but on likely harm to group’s purpose. Therefore, objecting to a proposal equals a “not yet” to the proposal and a big “yes” to the group’s purpose. Objecting means to say “I deeply care about our shared purpose and that’s why I can’t say yes to this proposal yet. There is still something that needs to be addressed.” Hearing the yes in a no is a plot twist to many people, and it’s extremely liberating. And if you’re allowed to say no, your yes is really a yes.

If you are confident that any team member feels safe enough to object, it’s now safe to propose.

Dare to propose

In very horizontal organizations or teams (i.e. a commitment to not exert power on each other), I notice a tendency of people holding back proposals. They might throw out ideas but they don’t formally propose. Some people are intimidated by having to make a well-formulated proposal but more often, a proposal is perceived as “pushy”. They don’t want to push an idea onto the group; instead, they hope for a plan to emerge. Yet, in my experience, it’s a great service to the group if a proposal is made because it gives the group something to relate to, something to improve.

If you are confident that any team member feels safe enough to object, it’s now safe to propose. Your idea doesn’t have to be perfect (as objections will be raised, if necessary, to improve it). You don’t have to be a mind reader that finds the perfect plan that pleases everyone ? because it’s enough if no one has an objection for the proposal to pass. Consent makes it easier to propose and easier to act – with more opportunity to act, revise, learn and connect. The possibility to object creates a safety net that makes it safe to play.

Dare to be human

The truth is that none of us are good fortune tellers. Things are too complex and unpredictable to ever really know how an idea will play out.

The mindset around consent is that we can’t know and therefore experiment instead of over-analyzing the perfect plan. In consenting (or not-objecting), you’re not saying that the plan is brilliant, you just say it’s safe enough to try out.

This bias for action embraces the humbleness of “we all don’t know let’s just check out bases and try it out”. No one can be outvoted and later say “see, I told you”. With the requirement of everyone consenting to approve a proposal, we’re all in the same boat: all committed to the same purpose, all equally responsible for the outcome, and all in the same humble position of not knowing for sure. It creates shared ownership and buy-in. It creates psychological safety. It makes team work more rewarding and human.

Ted Rau is co-founder of the non-profit Sociocracy For All, coaching and teaching and networking sociocracy practitioners in for-purpose organizations of all types. He is co-author of the handbook Many Voices One Song. Sharing power with sociocracy published in 2018. A PhD linguist, his strength is in holding complexity and clarity; as a member of an intentional community, he cares about connection and healthy pragmatism. As an activist, he cares about integrity, shared ownership, and the commons. Ted’s view on the world is influenced by the fact that he is transgender and a parent of 5.

Contact Ted: ted@sociocracyforall.org

Believing in the value of partnerships includes among other things, learning about history; reflecting on and working to change social justice issues; and recognizing and appreciating your own worth. We need ways to configure ourselves in order to talk with each other, listen and share, and resolve problems. This is where I find the value of learning the practice of Sociocracy. Thank you, Ted for writing here! Thank you CPS, for this platform to share and learn.

I note the mentions of Non-Violent Communication in both Riane Eisler?s work and Ted Rau?s work.

Learning.

In bringing new proposals to a mixed group, I frequently run into the “who’s going to pay?” and “how much will it cost?” objections. These appear to be responsible, but ignore the costs of the existing systems. Admittedly, these are generalized discussions not focused on generating action solutions.

Another problem I encounter is the inertia effect of conventional, sound bite objections from those who don’t use Biocultural Partnership Dominator Lens tools for analysis and solution generation.

I get a lot of blank stares when I explain that I no longer use left/right, conservative/liberal, Republican/Democrat, etc., models any more.

It’s all part of the change process, so we keep plugging. I do appreciate these insights and will start incorporating them in my work.